As violent crime continues to fall, Detroit residents hail community bonds

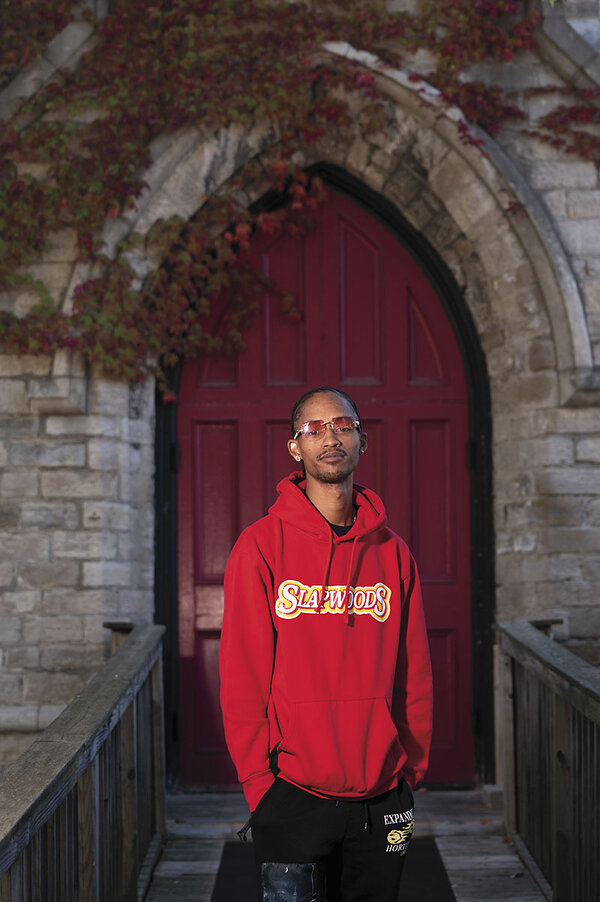

Dwight Roston stole cars as a teenager. He dropped out of school and spent his adolescence trying to avoid the police. The only reason he stepped into his neighborhood church on the east side of Detroit back in 2013 was to complete court-mandated community service – a condition of his second probation.

As his life was sliding downward, so was his city. Detroit careened into the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history, unable to pay liabilities of some $20 billion.

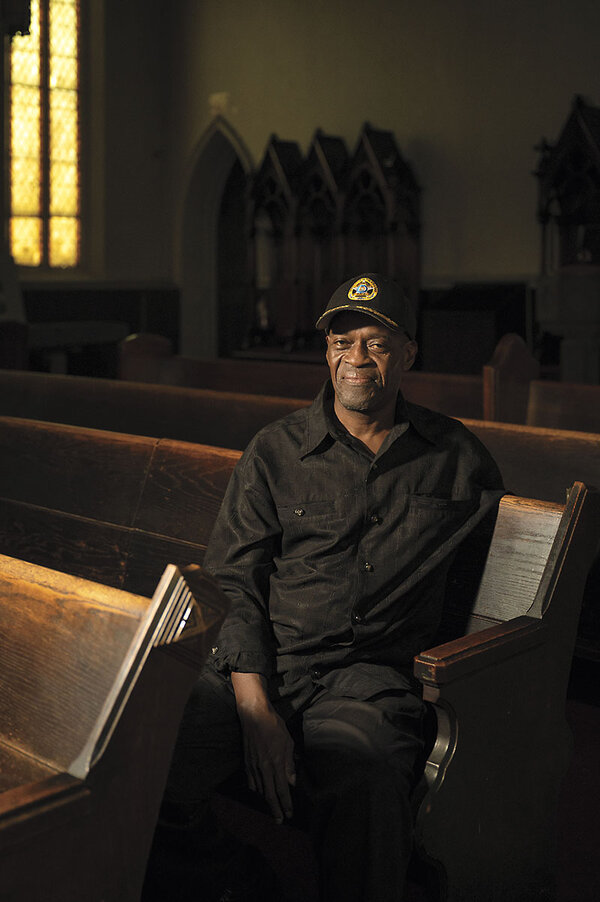

Most people wrote off Mr. Roston back then – just as they did his city. “He was an awful kid,” says the Rev. Barry Randolph, head of the Church of the Messiah Detroit, a congregation that welcomed the teen.

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump has deployed the National Guard to major U.S. cities to address urban crime. But as Detroit’s crime rate continues to fall, residents say what has worked is community connection and accountability.

This pastor was not most people, though. Pastor Randolph, who goes by Pastor Barry, or “PB,” had started a “Silence the Violence” march a few years earlier. He offered young Black men like Mr. Roston guidance and provided an alternative to the crime, violence, and drugs that helped make Detroit one of the most notorious cities in America.

The young men arrived at the church in Detroit’s Islandview neighborhood for skills workshops and other lessons to apply to their lives. Mr. Roston liked Pastor Barry because he didn’t drive a car or wear a suit. He wore a baseball cap and worked just as hard as anyone. He spearheaded a church-run “Grow Town,” that used urban gardens that teach farming techniques. He has also helped neighbors launch small businesses.

Dwight Roston poses outside the Church of the Messiah in Detroit, Oct. 8.

So, after his probation ended, Mr. Roston decided to stick around.

City leaders were often in the pastor’s office, he noticed. This both impressed and bewildered him.

“On paper, [these leaders] have all of this power and prestige, but they would come here and they would have meetings with Pastor Barry and ask him how to figure stuff out,” he says. “And to me, I’m just like, ‘Y’all get paid for this, and y’all can’t figure it out, and he don’t get paid, and he helping y’all figure it out.’”

Then one day, Pastor Barry invited the teenager to attend a meeting with city planners. They were talking about investing millions in new bike lanes. But Mr. Roston spoke up. He told the planners what the neighborhood really needed was improved public parks, including fencing and new nets for basketball hoops.

About a month and a half later, while Mr. Roston was riding around the neighborhood on his bike, he saw that a local park had been newly manicured, just as he’d suggested.

The Rev. Barry Randolph sits in the sanctuary of the Church of the Messiah in Detroit. The church has been a prominent driver of development in the Islandview neighborhood, providing affordable housing, free Wi-Fi, and other services.

“It was just a powerful feeling,” he says. “And it was good to realize that a lot of the things we complain about, if you are invited to the meetings, or if the meetings are open, those things that you have to say can actually impact the community.”

That’s how he came to trust Pastor Barry, who was leading him and so many of his friends out of trouble and into the pews of this community-building church.

At the same time, it turned out, the city of Detroit was crawling back from its own brink.

The specter of the National Guard

The safety of the American city has become a critical question as President Donald Trump deploys National Guard troops around the country. His administration’s stated aim is to battle urban crime.

“We’re going to save all of our cities, and we’re going to make them essentially crime-free,” Mr. Trump said from the Oval Office on Oct. 15. “This is an amazing thing. And we’re just at the start. We’re going to go into other cities that we’re not talking about purposely. We’re getting ready to go in.”

So far, the president has authorized deployments of troops to fight crime or temper what he says are violent protests in Portland, Oregon; Chicago; and Washington, D.C. – though each city has sued. In September, Vice President JD Vance offered to send the National Guard to Detroit, too.

An abandoned house stands in Detroit’s Islandview neighborhood.

Later in October, as leaders in Portland and Chicago pushed back against the president’s deployments to their cities, leaders in Detroit gathered for a news conference at police headquarters to underscore how much Detroit has been improving in recent years, especially when it comes to crime.

Back in 2013, the violent crime rate in Detroit was the highest among large U.S. cities, more than five times the national average. There were 333 criminal homicides that year, also marking the highest homicide rate in large cities: 48 per 100,000. (That year, the homicide rate in New York City was 4.)

Over the past few years, however, the homicide rate has dropped dramatically. In 2024, there were 203 murders in the city – a 39% decline from 2013 and the lowest number recorded since 1965.

Detroit property values also increased significantly in 2024, even after nine straight years of appreciation. Last year, the city’s total property values surpassed $10 billion for the first time since 2008. And according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent estimates, the city saw an increase in population in both 2023 and 2024.

At their news conference, city leaders said homicides were down 15% in the first nine months of 2025 compared with last year. Nonfatal shootings, too, dropped by 22%.

The Monitor asked Mayor Mike Duggan, a political independent first elected in 2013, whether the National Guard would be needed to continue these reductions in crime.

The Islandview neighborhood is lined with large historic homes. The Church of the Messiah has helped drive the renewal in this part of Detroit.

“I am a great believer that the way you reduce crime in the long term is, you change to a culture of accountability,” he said, flanked by a group of leaders that included police Chief Todd Bettison, City Council members, circuit court judges, and crime intervention groups. “You change an individual’s decision-making so that they don’t pack the gun in the first place.”

Crime is falling for a number of reasons. But the leaders here at police headquarters attribute Detroit’s recent successes to a commitment to working together from the bottom up.

Political leaders, police, and judges have cooperated with grassroots community organizers and faith leaders, creating a more unified effort to seek both swift justice and community healing in Detroit’s most troubled neighborhoods. That has built greater trust, they say, between them and the people they serve.

For many Detroiters, the city’s “comeback” is not an act of force, but a collection of choices made by those who refused to give up on their city – and refused to leave.

“This is how we rebuild our communities,” Pastor Barry says. “You turn the people around by providing opportunity, bringing out their humanity, meeting them where they are, and helping them get where they need to be.”

The success of “community violence intervention”

The basement of the Church of the Messiah is dubbed the “War Room.”

The neon-lit room has a dry-erase board packed with the month’s planned activities. It is here that Pastor Barry and community members plan strategies to battle the problems in their neighborhood. He doesn’t care who arrives or where they come from. He doesn’t care if they come to church, or if they even believe in religion.

Mr. Roston first learned about video production here. It helped him land a gig working for PBS. (He also got noticed during his adult baptism at the church, and a visitor that day helped land him another gig as a model during Detroit’s fashion week.)

Frank Cody High School students pray in a “trust circle” after playing basketball with FORCE Detroit, Oct. 7.

It’s here where community members incubate ideas for microenterprises, where they meet with city and state officials to share ideas about safe community spaces, and where leaders have organized their annual Silence the Violence march each June to honor victims of shootings. And it’s here that Pastor Barry says FORCE Detroit, one of the city’s most successful community violence intervention groups, was born from what had been ad hoc, grassroots organizing. (FORCE stands for Faithfully Organizing Resources for Community Empowerment.)

It is one of six original groups organized to work in the most violent pockets of Detroit. (A seventh was added this year.) Each received municipal grants from the city’s federally funded ShotStoppers program. In 2024, FORCE Detroit earned an additional performance grant of $175,000 after it helped achieve a 72% reduction in homicides and nonfatal shootings in its area from April to June. Overall, homicides fell by 45% in the 22 square miles Detroit’s Community Violence Intervention (CVI) groups served.

Across town from the Church of the Messiah, FORCE Detroit is at work in its neighborhood on a recent school day at Frank Cody High School. Staff members comb through the cafeteria to get sign-ups for a pickup basketball game during lunch.

With the gym doors locked by a security guard behind her, Taylor Lockridge, a trained violence interrupter known as “Coach Tee,” blows her whistle and asks the two dozen boys to get playing.

But her real coaching happens in the bleachers, as she inches next to a young boy with a mop of hair and a swollen eye. He is 13 years old, just out of middle school.

“What’s the beef right now?” Coach Tee asks him, trying to get a pulse on the kinds of rivalries that might spiral into violence. He mumbles an answer, trying to avoid her questions, until she tells him she knows his gang name. He finally perks up.

“He just said it out his mouth that he’s looking for rank, which for them means moving up on the chart,” Coach Tee says. “And the only way to do that is by killing somebody, beating somebody up, stealing, jumping someone – terrible things,” she later explains, after the bell for class rings. “I said, ‘Let’s change that there, please.’”

Taylor Lockridge, aka Coach Tee (left), stands with a staff member talking with a Cody High School student. FORCE Detroit is a community violence intervention program that works with young people and families in higher-crime neighborhoods.

Mike Peterson, the head of CVI programs for the city, says messengers like Coach Tee carry out the work critical for change. “Credible messengers are really trying to change that idea, and that narrative, around, ‘Oh, it’s just Detroit. Violence is OK.’ No, it’s not, and those are the sort of things that our groups are able to [communicate].”

Coach Tee, whose group with FORCE Detroit works with residents of the Warrendale and Cody Rouge neighborhoods, near where she grew up. She asks the ninth grader with the swollen eye to come back next week. “You gotta change that mindset and that narrative,” she says before her next group of players arrives.

The federal funding FORCE Detroit and other CVI groups have been getting, however, is about to dry up. As part of its efforts to slash funding for a host of overseas and domestic programs, the Trump administration is bringing to an end the Biden-era support for such violence intervention efforts.

In April, the Department of Justice notified FORCE Detroit it would no longer receive its federal grant funding. In May, the organization joined four other nonprofit groups to sue the U.S. government for not following federal protocols. The case was dismissed but is on appeal.

In July, the Trump administration ended the $158 million in grants allocated for gun violence prevention programs around the nation. Detroit’s ShotStoppers program had received $10 million previously. In October, the Michigan legislature approved some $95 million in public safety for cities with the highest crime rates, and Detroit’s leadership has said it will use that money to expand its CVI programs.

“If you don’t have great cities, you won’t have great nations.”

Beginning in the late 1960s, Detroit experienced one of the most prominent examples of “white flight,” or the out-migration of white residents from urban America. Its population was nearly 2 million in 1950, falling about 68% over the decades. In 1950, white people made up 84% of Detroit’s residents. Today, they make up 11%.

“Only the people who truly loved Detroit stayed around.” – Olayami Dabls, a longtime Detroit resident and artist. Mr. Dabls sits in his MBAD African Bead Museum and store, near where he has created a large outdoor public art installation.

As residents and businesses fled, thousands of houses were abandoned, and home values plummeted. Black communities, already marginalized by the redlining that excluded them from federal home loan guarantees dating to before World War II, were left in neighborhoods without a solid tax base – and with less city support for the most basic public services.

As Detroit descended toward bankruptcy in 2013, police Chief Bettison was a police commander, and he remembers streetlights that hardly worked. Some 45,000 homes were abandoned. There were few parks, just vacant lots with grass so high no one could play in them, he says. It took on average an hour for police to show up for emergencies.

Standing as an emblem for American urban decay was the city’s former train station, Michigan Central Station. Its broken windows haunted the city.

“It was painful,” says Chief Bettison. “It was embarrassing.”

The strategies for Detroit’s emergence from bankruptcy, known as the “Grand Bargain,” were hammered out in 2014. They included an unprecedented show of philanthropy.

“If you don’t have great cities, you won’t have great nations,” Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, famously said. “Detroit is a metaphor for America, for America’s challenges and America’s opportunities.”

In 2018, Ford Motor Co. purchased Michigan Central Station for $90 million with plans to redevelop it into a technology hub. The company has spent nearly $1 billion to restore the old station, which officially reopened in 2024.

Olayami Dabls’ “An-Kisi” public art piece is a building covered in tile and mirror mosaic.

Real estate billionaire and mortgage lender Dan Gilbert, founder of Rocket Cos., has been the biggest player in the revitalization of downtown Detroit, says Glenn Stevens Jr., chief automotive and innovation officer at the Detroit Regional Chamber. Mr. Gilbert’s venture group was behind the construction of a new mixed-use skyscraper, Hudson’s Detroit, the first built in the city since the 1980s. General Motors is planning to relocate its global headquarters here this year.

“So it’s very emblematic,” says Mr. Stevens, as America’s automakers help revive the once industrially powerful Motor City.

A comeback? These proud Detroiters never left.

The billion-dollar developments in the 7.2 square miles that comprise Detroit’s bustling downtown, Midtown, and Corktown are usually the main focus of stories people tell about the city’s dramatic turnaround.

But Detroit sprawls across 139 square miles. And the “comeback story” has an inherent tension in it: Tens of thousands of people never left the city in the first place.

Long before Detroit started building glittery skyscrapers again, Olayami Dabls was building his own gleaming buildings.

In 2002, Mr. Dabls opened the MBAD African Bead Museum, filling an expanse of open fields and abandoned buildings with public art. Plastered to the installations’ buildings are shards of mirrors that glint in the afternoon sunlight, reflecting not only Detroiters but also the city around them.

Mr. Dabls is among a generation of artists who flourished here in the 2000s and 2010s. As housing costs cratered, new talent flocked to the city from around the country, and many Detroit-based artists, like Mr. Dabls, stayed. “Only the people who truly loved Detroit stayed around,” he says.

Detroit Police Chief Todd Bettison speaks at a news conference at police headquarters in Detroit, Oct. 6. Chief Bettison announced a significant decline in violent crime so far this year.

Those people are the subject of a new documentary, “Resurgo Detroit,” directed by Stephen McGee, who moved here in the early 2000s after buying a home for $1. Detroiters who remained here, weathering a bankruptcy that left them without many city services and with a national narrative that maligned their city as a failure, have rejected the idea that Detroit has “come back.”

Detroit’s poet laureate, jessica Care moore, who produced “Resurgo Detroit,” says that is important for newcomers to remember. It’s a theme she returns to often in her work. “We may have abandoned homes but we / are not an abandoned people. / I hear outsiders talking about a new Detroit but I / remember the beauty of old Detroit,” she once wrote in a poem titled “You May Not Know My Detroit.”

“I ain’t mad at [newcomers] as long as you come with respect and don’t forget about the people who were here,” Ms. Care moore adds.

Sheree Walton, the president of the Church of the Messiah’s first housing project to buy and restore a burned-out building next to the church, looks out of a window and recalls Islandview’s abandoned lots with “grass that was higher than we were.” She has helped revitalize this neighborhood for decades.

“I hate the word ‘comeback,” says Ms. Walton. As a graduate of urban planning, she has mixed feelings about Detroit’s downtown development. “This revitalization cannot be successful without everyone having

equitable and affordable housing, because a lot of societal ills start with a lack of safe and affordable housing.”

As property values here have ballooned, it has created both opportunities and squeezes. Mr. Roston says he bought his home for $25,000 in the 2010s, and its value has increased tenfold.

Still, about a third of renters in Detroit spend between 31% and 50% of their income on housing – a benchmark making them “cost-burdened” under federal definitions. The median household income in Detroit proper stood at $36,500 a year in 2022, compared to $67,000 in the state. Homeownership remains out of reach for many.

Today, new units owned by the church’s housing development program have sprouted throughout Islandview, and the church has become the largest economic developer in the neighborhood. It has rehabilitated 214 apartment units and owns 49 vacant lots.

Stately Victorian mansions once owned by auto barons in this portion of Detroit’s east side were left abandoned with boarded-up doors and broken windows. Today, newcomers are purchasing and rehabilitating them. Developers keep calling about the land it owns, says Pastor Barry.

Mr. Roston and his friends see the rise of Detroit reflected in their own lives. “We came with problems, and then we started coming up with ideas,” he says.

Markuis Cartwright (right) hugs Paul Jones in the Rev. Barry Randolph’s office at the Church of the Messiah in Detroit.

Lounging in Pastor Barry’s office at the church on an October morning, a group of young men echoes this sentiment. Paul Jones says that, at age 15, he looked in the mirror and told his reflection that he didn’t think he would live another year. “I see myself very much in the city of Detroit – being down, being battered, beat up, talked down on,” Mr. Jones says.

But it was at that moment he first felt God calling him to the faith he holds today. During his senior year of high school, after his mother died, his middle school best friend, Giovanni Jackson, who used to deal drugs, had been embraced by Pastor Barry. He encouraged Mr. Jones to come to church.

Both are now successful. Mr. Jones works in real estate development and serves on the board of the church’s housing development corporation. Mr. Jackson turned a passion for cooking into a small business, Giovanni’s Seasoning.

Markuis Cartwright, sitting quietly among the group this morning, works at Amazon and at a local youth nonprofit. But he aspires, one day, to be mayor of Detroit. So Pastor Barry put him behind the podium at the annual Silence the Violence march.

“Tap into their warrior spirit,” Pastor Barry says. “Take activism and spirituality, and make that your purpose and your vision.”

“You don’t need the National Guard to go into cities and do these things,” he adds. “We did this.”

Responses