How one Michigan town is putting partisanship aside in pursuit of clean water

With two Trump-Vance campaign signs planted in their front yard, James Ash and his wife, Sara, might not seem like a welcoming audience for liberal activists handing out flyers.

But Mr. Ash says that when he heard the state had tested the water supply of Three Rivers, Michigan, and found lead, he knew he had to take action.

It didn’t matter whether he was on the same political team as the person handing out the flyers. In fact, he offered to take campaign flyers to the union hall at his workplace – a local auto parts manufacturer. Then he spread the word about the possible lead contamination through his fellow United Auto Worker members.

Why We Wrote This

Democrats and Republicans are at odds nationally, as the continued government shutdown shows. But in Three Rivers, Michigan, local leaders are setting aside differences for the common goal of real problem-solving.

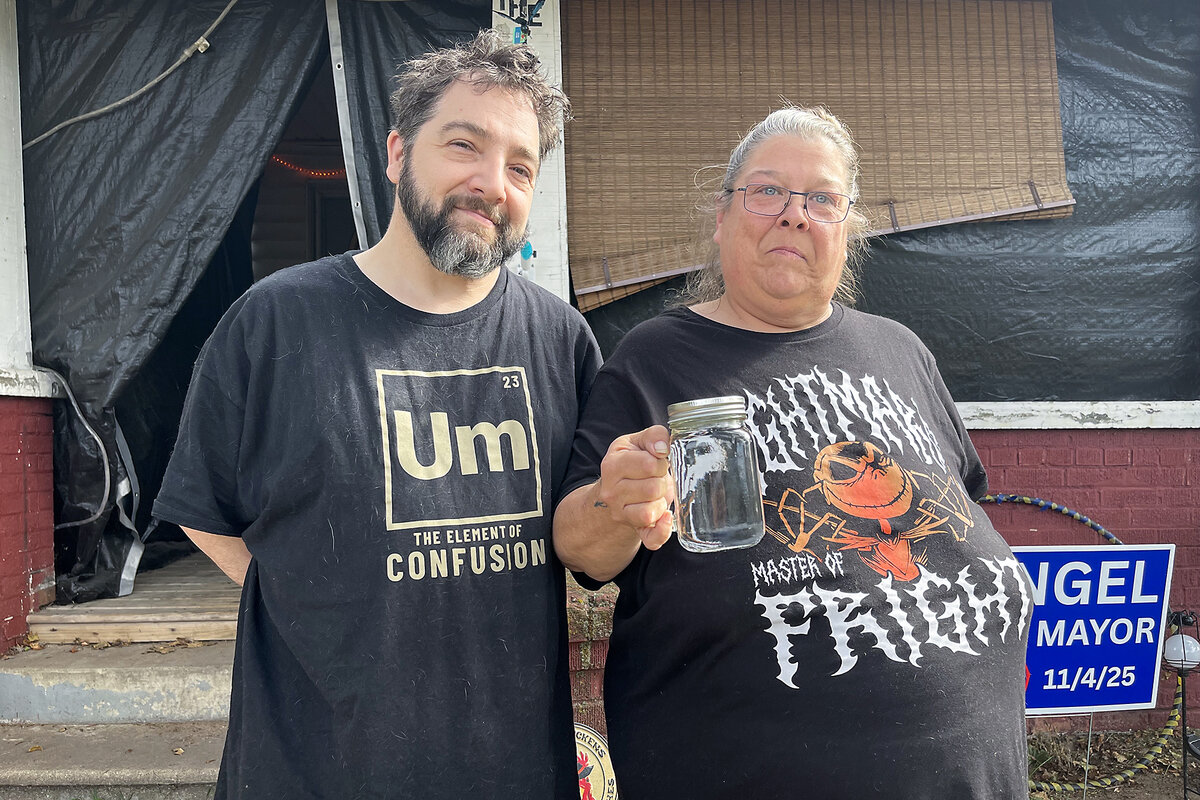

“Water is the life force; without water, we all die,” says Mr. Ash. As he talks, sitting on his front porch, Sara Ash fills a mason jar from the tap. It’s clear fluid, but that doesn’t bring any comfort. “They tell us our pipes are fine,” he says. “I know the state is taking frequent tests of the water. That’s a start, but it’s not helping the water.”

Mr. Ash says water isn’t a partisan issue. In fact, he has found common ground with Three Rivers residents whose views span the political spectrum. When it comes to water, he says, “We are joined together.”

Scott Baldauf /The Christian Science Monitor

James and Sara Ash show a glass of water from the tap of their home in Three Rivers, Michigan. They joined a clean water campaign after they learned of testing showing high levels of lead in the city’s water system.

The residents’ cooperation has mostly involved spreading the word and showing up together at City Council meetings, trying to speed up what they say is the city’s slow response to a problem that the mayor says affects an estimated 10% of the 3,500 homes here, where water is at the heart of the community’s very identity.

Three Rivers, located at the confluence of the St. Joseph, Rocky, and Portage rivers, is committing money to try to fix the problem – partly due to pressure from this politically diverse group of local residents. Mandated by the state to fix the problem in 20 years, Three Rivers came up with a plan to meet that requirement.

In the context of a federal government shutdown now in its third week, the Three Rivers clean water campaign offers a glimmer of hope. Unlike in the nation’s capital, where Democrats and Republicans refuse to speak to each other, people in Three Rivers are finding common ground on clean water.

What’s happening here is a hallmark of Michigan politics, says David Takitaki, professor of political science at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan. He describes a “kitchen-table pragmatism” that thrives in a state with cities that lean Democratic, and rural areas “permeated with blue-collar working class unionism.”

“Local politics rarely gets as hyperbolic as it does at the state and federal level,” Professor Takitaki says. “The main interest is about running your community. Nobody is tying things to the abortion issue. Nobody is trying to make you hate others. It’s more collegial and communal.”

The downside of local politics is that it is often ignored, he says, even by voters. The upside is that flying under the radar “keeps it from being a blood sport,’’ he adds, “if we are able to get back to [the idea of] government as problem-solving and have discussions instead of tearing each other apart.”

Urgency to fix the problem

It was just over two years ago that the state discovered the source of the lead contamination was in the lateral pipes that supplied water to each house.

People of all political stripes wanted the city to replace those pipes at once. The estimated cost: $4.2 million.

Mayor Tom Lowry is seasoned enough to be considered an elder statesman, having served 13 two-year terms as mayor. By now, he says, he has a feel for what the public wants, what the public can afford, and what they would be willing to pay for. He concludes: They would not be willing to pay higher taxes to replace the lead pipes in Three Rivers, and many couldn’t afford it.

“We have a higher than average number of people who are two paychecks away from financial disaster,” Mayor Lowry says. “We lost two companies over the last five years that employed 100 people each. As a result, we have a lot of people on the edge of poverty.”

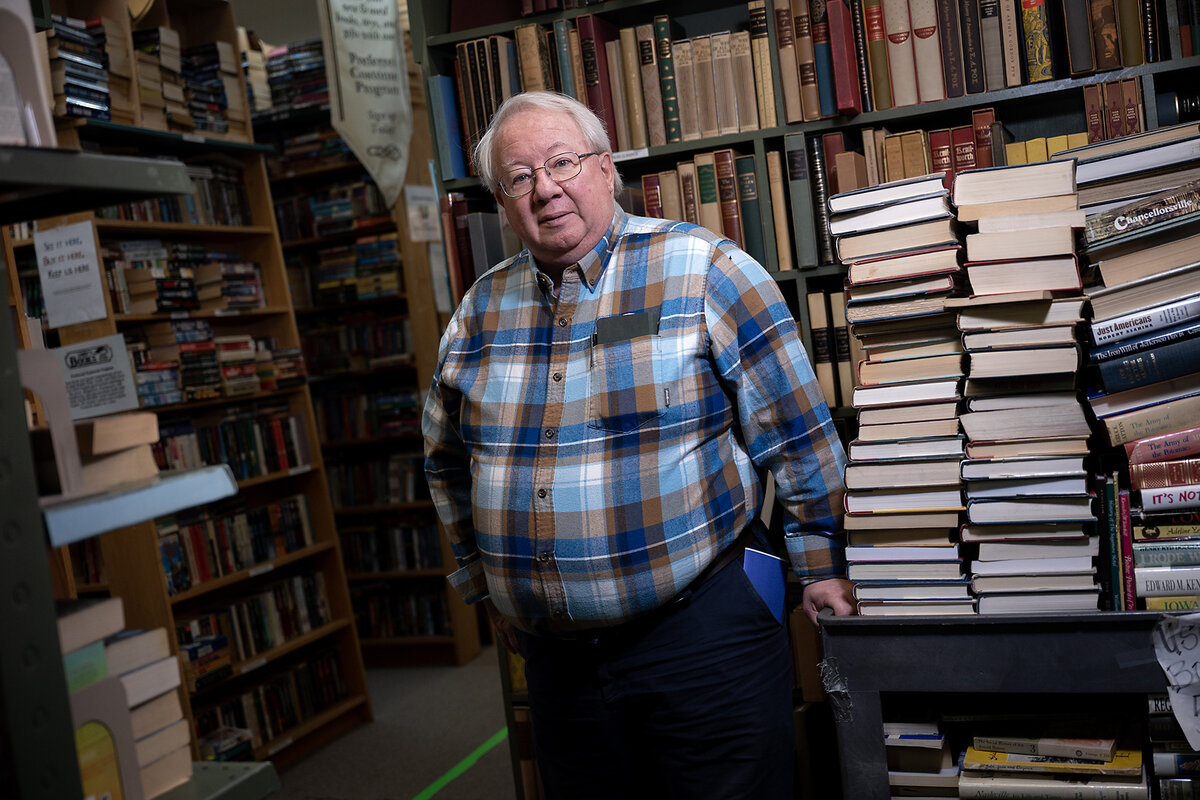

Tom Lowry, decades-long mayor of Three Rivers, Michigan, poses on Oct. 10, 2025, in the bookstore he owns in town. After unsafe levels of lead were discovered in the water system due to aging pipes, Mr. Lowry says Three Rivers can repurpose an existing bond and put it toward fixing the lead problem.

To Mr. Lowry, it’s clear that the most affordable solution to the lead problem is to repurpose an existing $2.7 million bond meant for street and wastewater system repairs, a measure that voters supported in recent elections. But Mr. Lowry keeps hearing complaints that City Hall is taking too long to resolve the issue.

“At public meetings, I keep repeating the truth,” the mayor says. “It can be ugly and nasty, but through repetition of the facts, some start out angry, but most come around to a working relationship.” Even when clean water activists did picket and attend City Council meetings, he says, they were largely cordial and mainly came to listen, not shout.

The plan is that when streets are being redone, the city will test water lines and replace those that have lead. In addition, the city has begun to add a chemical called Aquadene to the water supply, which coats the pipes and reduces the leaching of lead into the water. Mr. Lowry says that tests show the lead levels are coming down.

Casey Tobias poses in the Homeless Outreach Practiced Everyday free store on Oct. 11, 2025, in Three Rivers, Michigan. Tobias is one of the activists who joined forces to demand local government move quickly to address lead in the water supply.

For Casey Tobias, the lead problem isn’t being solved fast enough.

Ms. Tobias is a fireball of a woman with a tendency to pull people into her orbit. She attends the Trinity Episcopal Church, sells dried herbs at the farmer’s market, and runs a donations shop that benefits the poor and the unhoused in Three Rivers. She learned about the city’s lead contamination by word of mouth. Someone donating clothes was complaining about being unable to find water filters. Ms. Tobias asked, “Filters for what?”

By the end of the conversation, Ms. Tobias was a determined activist. In a short time, she was walking the streets alongside others, knocking on doors, and handing out informational flyers.

“I think the entire city is Republican,” says Ms. Tobias, who considers herself liberal, but says that she can work with anybody. “I don’t care about any of that. We all agree on water.”

Soon, she and other activists organized brainstorming sessions to help concerned citizens understand the scope of the problem and possible solutions. At one event, the organizers seated participants in a circle of chairs, allowing them to see each other and feel a sense of connection. A local bakery provided cupcakes. A guitarist played mood music.

Ms. Tobias says the organizers had to add another ring of chairs, and then another, as participants filed in.

“They may have been Democrats, more likely Republicans, but they all felt like they were contributing to something,” Ms. Tobias says. “Many of them said, ‘It’s just not working the way it should.’ Look, we have to be in this together. If we can’t get together over water, then God help us.” (In the 2024 presidential vote, St. Joseph County – which includes Three Rivers – leaned heavily Republican, with 66% voting for the GOP, and 32% voting for Democrats.)

Ms. Tobias said people told her that joining forces on the water issue was pivotal for the community. “All of us felt there was a light at the end of the tunnel,” she says. “It was proof that we could come together across political boundaries.”

Coming together

John Byler has lived in Three Rivers for more than 30 years. Just behind his house are three of the city’s wells, and the St. Joseph River behind them. Alongside his job at the local farm supply store, his volunteer work with the Methodist church, his small cattle operation, and his duties as a clan chief within the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band, Mr. Byler found time to join Tobias and others on the clean water campaign.

John Byler poses on his property on Oct. 10, 2025, in Three Rivers, Michigan. After unsafe levels of lead were discovered in the Three Rivers water system due to aging lead pipes, residents have joined forces — across partisan divides — to demand solutions from their local government.

Mr. Byler says people didn’t talk about lead in the water until it was discovered in Flint, Michigan, in 2015, and then the state warned that this problem could be much more widespread. Now the most heated arguments occur on Facebook, but in public meetings, people just want to find solutions. “It’s just a matter of getting them to adjust the 20-year plan and to expedite some of those houses that are in greater need.”

Among those pulled into Ms. Tobias’s orbit was Angel Johnston, who became so energized by the clean water campaign that she decided to run for mayor against Lowry on the water issue. Election Day is Nov. 4, and Ms. Johnston has been busy knocking on doors and promising to accelerate the lead pipe removal.

“Everyone is concerned about the water,” says Ms. Johnston, who works for a smart-home integration company. “They ask, ‘Why is our water bill so high? Why can’t we drink the water?’ Everyone says, ‘What are you going to do about it?’”

Angel Johnston poses on Oct. 11, 2025, in Three Rivers, Michigan. She is running for mayor, challenging incumbent Tom Lowry, largely because she feels city government has failed residents in addressing the problem of lead in the water supply.

Mayor Lowry would note that under his leadership, the city has a plan in place. But Ms. Johnston is finding support, too – including from James Ash, the auto worker. He has placed her sign “Angel for Mayor” in his front yard, next to his Trump-Vance signs.

“I don’t consider myself from any party,” Mr. Ash says. “I go with what feels right and I stick with my views.”

He acknowledges the city is taking action to provide clean water. “Now the city is taking baby steps. They are doing something, but not at the rate I’d want them to go.”

Baby steps or not, he says, it’s a path of progress.

Responses