Why Rome’s origin myth leaves more questions than answers

It is unusual for a city to boast a true founding event. Such occasions are rare, mostly taking place when a conqueror decides to create a city bearing his name. This was the case with Alexander the Great, who established more than 20 cities in the fourth century B.C. On the other hand, Rome, much like Athens, was more likely the result of synoecism—the gradual aggregation of neighboring villages that, driven by the need for defense and trade, eventually coalesce into a single community under a monarchy. However, the legends of Rome’s founding are far more riveting.

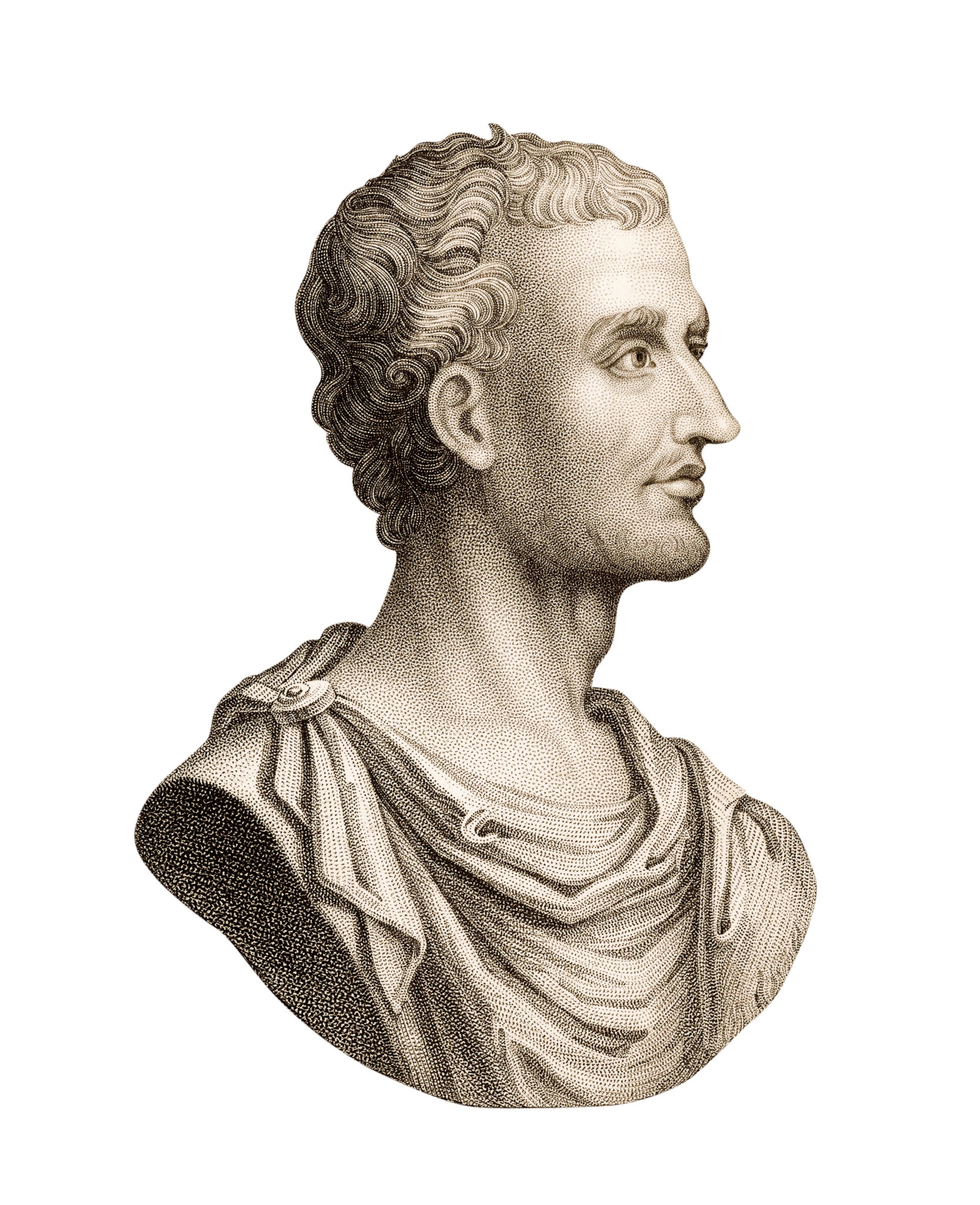

The wisest words on the matter come from the Roman historian Livy, in the opening of his monumental Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City): “I intend neither to affirm nor refute the legends concerning the time before the foundation of Rome or the foundation itself, for they are poetic tales rather than reliable evidence of historical events. We willingly grant the ancients the custom of ennobling the origins of their cities by blending human deeds with those of the gods. And if ever a people had the right to make sacred its origins and tie them to the divine, it is surely the Romans.”

The first to express skepticism about the wealth of myths surrounding Rome’s birth were, in fact, the Greek and Roman historians who passed those stories down to us. These scholars lived in an era when any writer could draw on a multitude of oral legends that had sprung up to justify and glorify the power achieved by Rome over the centuries.

We must begin precisely from these mythical traditions when reconstructing the history of the city’s founding. By comparing the various accounts available to us, we can discern how much truth lies behind the lore that hints at a kind of civil war between two brothers,Romulus and Remus, who had previously been united in a quest to bring justice to their family.

ROME’S RIVER, ROME’S FOUNDERSDiscovered in 1512 in Rome’s Field of Mars, this circa first-century sculpture is an allegory of the Tiber River, on whose banks the twins Romulus and Remus were abandoned. Louvre Museum, Paris.

SCALA, FLORENCE

The earliest traces of the myth

Although it refers to events that occurred three centuries earlier, the story of Romulus and Remus began to circulate around the fifth century B.C. within Greek circles clearly impressed by the extraordinary rise of what had, until recently, been merely an unremarkable town on the Tiber River. At the time, rumor had it that the founder was a certain Rhomos, known to the Romans as Romulus. Over the following century, the two figures appeared to coexist and, in time, Romulus began to be portrayed as Rhomos’s grandfather. After another hundred years, the transformation was complete: Rhomos had disappeared from legend, with the arrival of Remus, Romulus’s twin brother. Greek philosopher and historian Plutarch, who lived between the first and second centuries A.D. and was the author of a biography on Romulus, writes that the first person to create a cohesive narrative about Rhomos and his descendants was Diocles of Peparethus in the third century B.C. He was soon followed by a contemporary author, Quintus Fabius Pictor, whose work, the Annales, has survived only in fragments.

(Is this the real reason the Roman Empire collapsed?)

As for the existence of the twins and their tumultuous story, the oldest surviving testimony is a group of statues depicting a she-wolf suckling two infants. They were erected in 296 B.C., during the Samnite Wars, to commemorate the appointment of two brothers—Quintus and Gnaeus Ogulnius Gallus—as aediles (magistrates).

In short, the creation of the two figures of Romulus and Remus took place within a Greek cultural context. For this reason, references to the gods of Olympus and a legendary event of the pre-classical period—the Trojan War— was an inevitable part of their myth. During the Augustan age, several authors attempted to reconstruct the epic saga, from Marcus Terentius Varro, whose historical work Antiquitates is now entirely lost; to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, with his Roman Antiquities, of which the first nine books survive; and, finally, to Livy, whose Ab Urbe Condita, Latin for “from the founding of the city,” originally consisted of 142 books, 35 of which have been preserved in their entirety. The first 10 volumes by the Roman historian, who lived at the turn of the first century, outline a coherent account of the myth surrounding Rome’s founding. Varro is often credited with proposing an official date for the founding of the urbs (or city): April 21, 753 B.C., corresponding to the final face-off between Romulus and Remus. This date was calculated by attributing 35 years of reign to each of Rome’s seven kings before the Republic’s establishment in 509 B.C., as determined by the scholar. Other authors proposed different calculations, but Varro’s chronology prevailed.

Trojan ancestors

It all began with Aeneas, the Trojan hero who fled the burning city with his elderly father Anchises on his shoulders and his son Ascanius, or Iulus, at his side. His escape is traced back to 1184 B.C., more than four centuries before the myth of Romulus and Remus, but in legends time flows quickly—or not at all. When Emperor Augustus tasked the prominent poet Virgil with composing a piece celebrating the origins of the gens Julia and the Augustan restoration, the poet chronicled the wanderings of the Trojan hero, making them strikingly similar to those of Ulysses. At the end of his journey, Aeneas is said to have landed on the shores of Italy where, in the region corresponding to the area of Latium, he fought with the native peoples. He eventually made peace with them, sealed by his marriage to Lavinia, daughter to King Latinus, and by the founding of a new settlement, Lavinium. The myth continues with the exploits of Ascanius, or Iulus—whether they were the same person or the two sons of Aeneas, one born from Creusa in Troy and the other from Lavinia in Latium, remains unclear—who, 30 years later, is said to have founded his own city, Alba Longa, near today’s Castel Gandolfo, though historians and archaeologists have never been able to pinpoint it with any certainty.

ROME’S OTHER ORIGIN STORYAeneas flees Troy with his father on his back, followed by his son, Ascanius, in G.L. Bernini’s 1619 sculpture. Also known as Iulus, Ascanius was believed to be an ancestor of the Roman people, and of Julius Caesar. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

G. DAGLI ORTI/DEA/ALBUM

In any case, Aeneas’s son founded a long-lasting dynasty that would endure for several generations. Centuries later, Proca, the eleventh or twelfth descendant of Ascanius, devised a curious yet deceptive system to have his two sons share the rule of the kingdom. He bequeathed his kingdom to the first, Numitor, and granted the royal treasury to the second, Amulius. But while a kingdom without money is worthless, money can buy a kingdom. This inevitably led to the very civil war Proca had so desperately sought to avoid. Amulius managed to seize the throne, reducing his brother to a subordinate role. As a precaution against any future dynastic threats, he decided to murder his nephew Aegestus and force his niece, Rhea Silvia, to become a vestal virgin, thus condemning her to perpetual chastity.

(How much do you know about the Roman Empire?)

Descendants of Mars

The vestal virgins served for 30 years, during which time they tended the sacred hearth of Vesta, Roman goddess of the home and family. According to Livy, Amulius’s plans did not go as expected. Claiming to have been impregnated by the god Mars, Rhea Silvia gave birth to twin boys. Some versions suggest she was the victim of rape. Livy comments, “neither gods nor men were able to protect her and her children from the king’s cruelty.” It is said that, in a fit of rage, Amulius intended to kill his niece for the heinous crime of breaking the vestal vow of chastity.

Indeed, this punishment was a well-established practice in Republican Rome, though certainly not in Amulius and Numitor’s time. According to the myth, the king ultimately yielded to his daughter’s pleas and had Rhea Silvia imprisoned instead. He then ordered that the newborn twins be drowned. However, his henchmen mishandled the task, merely placing the infants in a basket and setting it adrift in the stagnant waters left behind by a recent flooding of the Tiber. This image is a recurring motif in ancient traditions, symbolizing divine protection and predestination. Before the twins, for example, both Moses and Sargon of Akkad had been similarly saved.

SHE-WOLF OF ROMEOnce believed to date from the fifth century B.C.,the hollow-cast bronze she-wolf at Rome’s Capitoline Museums has, in recent years, been radiocarbon dated to the medieval period. It was donated to the people of Rome by Pope Sixtus IV in the 15th century, and the figures of the twins Romulus and Remus were added soon after. From the 1920s, Italy’s fascist prime minister Benito Mussolini regularly used this powerful symbol of Rome in state propaganda.

BRIAN JANNSEN/ALAMY/CORDON PRESS

Once again, the children survived. The basket eventually came to rest near the legendary Ficus Ruminalis. According to some authors, this fig tree was named for the ruminating animals that would gather beneath it; others claim the name derives from ruma, the Latin word for teat, which may have also inspired the twins’ names. Located at the foot of Palatine Hill, the tree became the setting for the story of a she-wolf who approached the infants to nurse them. Later, the wolf is said to have carried them to a cave known as the Lupercal, where the children were also watched over by a woodpecker—a bird sacred to Mars, their divine father.

The local shepherds who witnessed the scene interpreted it as a divine omen. Among them was Faustulus, a swineherd in Amulius’s service, who decided to take the twins and entrust them to his wife, Acca Larentia. While recounting this version, Livy hints that the tale of the she-wolf may be a metaphor concealing the true role of the woman, a courtesan. In Rome, sex workers in lupanars (brothels) were known as lupae or she-wolves.

Another version, reported by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, suggests that the twins were handed over to Faustulus by Numitor himself. According to this account, Numitor had replaced Rhea Silvia’s sons with other infants, deceiving Amulius into ordering their deaths.

THE EPIC OF ROMEThe first-century historian Livy, depicted here in a 19th-century engraving, is one of a handful of Roman authors who recount the story of the founding of Rome by Romulus and Remus. Historians trace the myth’s origins to the fifth century B.C.

SCALA, FLORENCE

Regardless, Romulus and Remus grew up to be strong and daring, known for their raids on neighboring villages—a common feature of life in the Latium communities of the time. They were often at the forefront of skirmishes between the shepherds loyal to Amulius and Numitor, respectively, who clashed over land and livestock theft. Eventually, Remus was ambushed and captured by Numitor’s men. Though the shepherds were required to bring the prisoner before Amulius for judgment, the king returned him to Numitor for punishment. Instead, Numitor took the opportunity to investigate the young man’s origins. According to Plutarch, Remus shared what little he knew of his own story with these words: “I will hide nothing from you, for it seems to me that you behave as a true king should; more so than Amulius. You listen and inquire before punishing, while he hands the accused over to the executioner without questioning.”

The recovery of Rome

Though still unsure of the young man’s identity, Numitor recognized in him a determined spirit capable of aiding in the recovery of his kingdom. Meanwhile, Romulus, who had gathered a band of shepherds, herdsmen, enslaved people, and fugitives to rescue his brother, approached Numitor. With his confirmation of Remus’s story, Romulus helped Numitor piece everything together. The deposed king recognized his grandsons, who now resolved to undertake the most prestigious of raids on his behalf: an attack on Amulius’s fortress. However, Amulius had already extracted the truth from Faustulus, and tried in vain to have the twins and Numitor arrested. Undeterred, the young men led their small army into battle. Their coordinated maneuver succeeded, allowing them to seize the royal palace, kill the usurper, reinstate their grandfather on the throne, and free their mother, who was still in chains.

THE FOUNDING MYTH IN FOUR SCENESThe story of Romulus and Remus is depicted on the rear side of the Ara Casali, an altar or base from the second century A.D. At the top, Mars meets the vestal virgin Rhea Silvia. In the second scene, Rhea Silvia appears again with her twin sons, Romulus and Remus. In the third scene, the children are depicted abandoned in the river; and in the bottom scene, they are suckled by the she-wolf. Pio-Clementino Museum, Vatican.

SCALA, FLORENCE

While one version of the myth portrays Numitor as the twins’ savior at birth, another suggests that the deposed king intentionally provoked the conflict among the shepherds to orchestrate the rebellion led by his grandsons. Thus, one tradition casts Numitor as a passive advisor, while another presents him as a cunning strategist who orchestrated his revenge from the shadows.

You May Also Like

Nonetheless, the two young men had no interest in awaiting their grandfather’s death to inherit his throne. Moreover, the inhabitants of Alba Longa were not particularly pleased with the unruly crowd gathered by the brothers to overthrow Amulius. At the same time, Romulus and Remus had earned a reputation as heroes, and many were eager to follow them, drawn by the hope of rich plunder, better homes than their current huts, and fertile lands for farming or pasturing their flocks. In the interpretation of the myth where Numitor himself acted as deus ex machina, he is said to have founded a colony and sent his grandsons to govern it, along with all the undesirables of Alba Longa and its surroundings. Alternatively, the undertaking may have followed a common custom of the time, wherein groups of young people were dispatched during the spring months to establish new settlements.

A single king

Trouble began from that moment on. In Latium there was no dyarchy like in Sparta, and so there could be only one king. “The two were twins, so age could not serve as a deciding factor” in determining who should wear the crown, explains Livy. The gods needed to be consulted, and a particularly vivid and colorful scene likely masked what was actually an inevitable civil war arising between the two contenders to the throne, both of whom claimed equal rights. According to tradition, the decision was left up to augury—the interpretation of omens based on the observation of birds, one of the most widespread ways of discerning the divine will. According to another version, the prophecy was decided by Numitor himself, whom the brothers had approached to settle their disputes. In any case, each chose a hill where he wished to found his city: Romulus the Palatine, and Remus the Aventine. Remus had a furrow plowed into the ground by the augur— the interpreter of divine omens—representing a sacred boundary within which to look for omens. The first to spot the birds, a flock of six vultures, was Remus, who had already begun celebrating his victory when Romulus spotted 12 of them. A new argument then arose over which brother the gods had designated king: the one who had seen the birds first or the one who had seen a greater number of them.

FRATRICIDEThis detail is from an engraving by Matthäus Merian the Elder that was published in Frankfurt in 1630. It depicts Romulus killing his twin brother, Remus.

ALBUM

Some ancient chroniclers even suggest that Romulus lied about the number he saw—or at least, this is what Remus believed. Dionysius of Halicarnassus recounts that Romulus tried to deceive his brother by calling him to the Palatine to announce that he had seen the vultures first. On his way there, Remus spotted six vultures himself. Twelve birds appeared at the very moment he asked Romulus how many he had really seen, and Romulus claimed they were precisely the ones he had seen earlier. Thus followed a clash between the factions supporting each twin, and Remus met his demise in the ensuing melee.

Another version of the story, also cited by Livy and with slight variations by Dionysius, attributes the death of Remus to his own instigation. Remus supposedly crossed the ditch his brother was digging to mark the boundary of his city—or simply the furrow traced with a plow in the ground—and Romulus did not hesitate to kill him, declaring, “Let the same fate befall anyone who dares to cross my walls!” Other sources, however, name Romulus’s foreman, Celer, as Remus’s killer, and the swiftness with which he fled to Etruria immediately afterward is said to have given rise to the very concept of speed ( “celerity,” “accelerate,” from the Latin celer). During the conflict—more likely a civil war, as Dionysius of Halicarnassus more clearly suggests—Faustulus, who had tried to act as peacemaker, also perished.

At that point, Romulus, after burying his brother on Aventine Hill, was free to complete the fortification of Palatine, the primordial nucleus of the city that still bears his name. It matters little whether he did so immediately or, as Dionysius claims, only after a long period of mourning from which he only emerged thanks to Acca Larentia.

Other origins of Rome

This is by far the most widely accepted account of the Eternal City’s founding, having eclipsed all others due to its epic nature and the wealth of challenges and rivalries it contains. Yet Plutarch, as well as Dionysius of Halicarnassus before him, asserts that other stories circulated in his time, suggesting that the Eternal City’s name did not derive from Romulus but from a Trojan refugee—a woman named Roma—who persuaded her community to settle permanently on the Latium coast. She even convinced the women to burn the ships so as to prevent the men from taking to the sea again. According to Dionysius, Roma married Latinus and bore Romulus and Remus, who named the city in their mother’s honor. Or else the name might derive from rhome, a word used by the Pelasgians, Indigenous people from the Aegean Sea and conquerors of the Latium region, to express the concept of “strength.”

CHILDREN OF MARSIn Livy’s account of Rome’s founding, the vestal virgin Rhea Silvia claimed the twin boys she bore were fathered by Mars. The god of war is depicted here in a circa second-century statuette. Louvre Museum, Paris.

H. LEWANDOWSKI/ RMN-GRAND PALAIS

Plutarch also records numerous traditions, many of which claim that Romulus and Remus were actually the sons or grandsons of Aeneas. Another story recalls the abduction and rape of the Sabine women by Romulus and his soldiers to increase the number of women in Rome. The most curious tale traces the twins’ origins back to the cruelty of the Alban king Tarchetius, who reportedly witnessed the ghost of a giant phallus emerging from a hearth in his palace. Plutarch recalls that according to this bizarre interpretation, a prophecy foretold that if a virgin joined with this entity, she would bear a famous son “renowned for his virtue, fortune, and strength.” The king ordered his daughter to lie with the ghost, but the girl passed the dubious honor to her maid. Discovering the deception, Tarchetius was about to execute both women when the goddess Vesta intervened. The women were instead confined to their home and sentenced to weave a tapestry they could not complete, as the goddess unraveled their work each night. From here, the story aligns with others: When the twins were born, the king handed them over with orders for the children to be killed. Instead, a man abandoned them along the Tiber, where a she-wolf cared for them, enabling them to later seek revenge against Tarchetius.

Although the myth of Romulus and Remus has endured throughout the centuries, concrete historical and archaeological evidence supporting it is sparse. The success and longevity of a people, a civilization, or a figure, inevitably give rise to myths and legends crafted to shape a predestined origin and past, legitimizing their right to dominance and fame. This is especially true for a political entity like Rome, which survived multiple incarnations—monarchy, republic, principate, Roman Empire, Byzantine Empire—for over two millennia, from 753 B.C., when the Assyro- Babylonians ruled in the East, to 1453, the year Constantinople fell.

This story appeared in the September/October 2025 issue of National Geographic History magazine.

Responses